Not to disappoint the astrology-lovers in the audience, but this piece won’t be diving into the origins of the sensitive and empathetic star-signs born in June and July.

Mostly because I know nothing about astrology, and would make a fool of myself trying to convince you otherwise. However, I do know that being born on June 23rd makes me a cancer sign, which I considered highly amusing when I started cancer treatment on my birthday in 2021. Was my birth an omen? A self-fulfilling prophecy?

I’m just kidding with the existential conspiracies, but I did find using “Oh, that’s because I’m a cancer” to be my favorite joke to bring out on the chemo floor. The nurses loved it! *editor’s note: they didn’t.

Okay maybe the nurses didn’t love it, but you know who might appreciate my levity given the situation? The ancient Greek physician Hippocrates (460-370 BC) (you know, THE hippocratic oath guy?) who is credited with the naming of the disease after examining a malignant tumor with spindly legs which had attached itself to it’s host. *editor’s note: he wouldn’t.

Karkinos is the ancient Greek word for crab, and also what Hippocrates would name this mysterious and aggressive disease that seemed like a parasite of the body’s own making. Later, Roman philosopher Celsus would adapt this word to Latin giving us the modern root word for cancer: Carcinoma.

There is some debate over whether Hippocrates named the disease after a crab because the tumor looked like a crab, had a hard shell like a crab, or hurt like the pincers of a crab. Either way, the associations are creative.

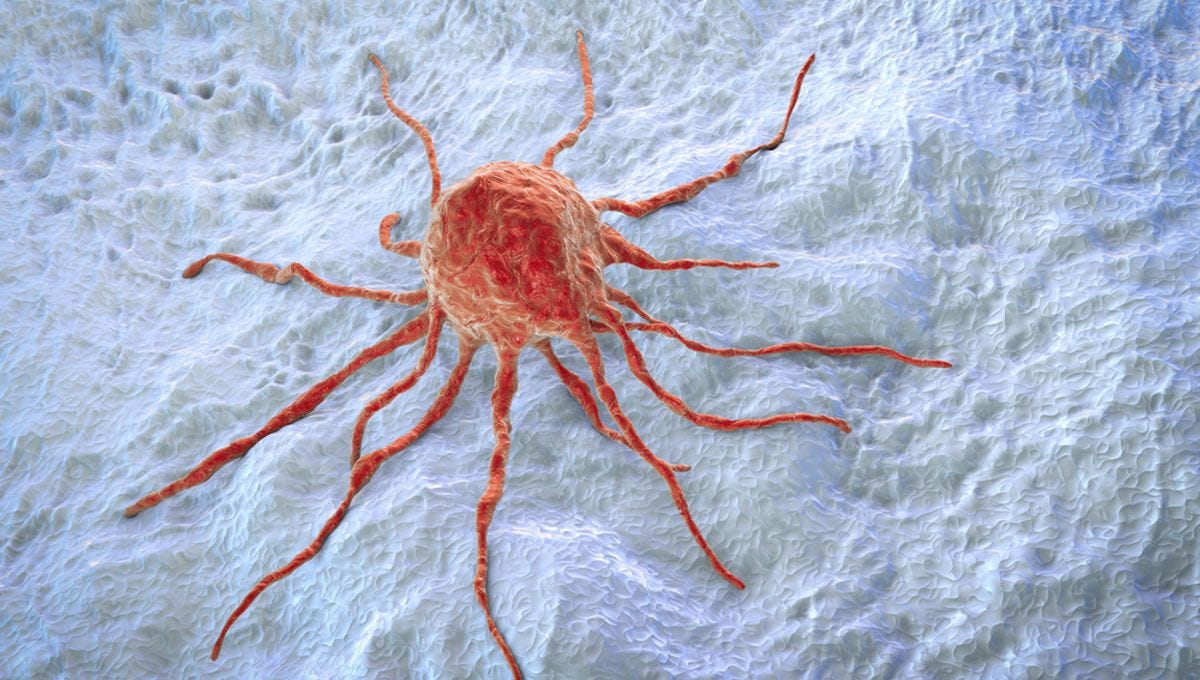

However, it is documented that 100 years later, a physician named Galen surgically removed a breast cancer tumor from a patient and began dissecting it. He wrote in his notes that all the veins and tributaries emanating out of the malignancy looked just like a crab's legs extending outward from its shell.

The first known recorded instance of cancer occurred in Egypt in 1600 B.C., but it was Hippocrates who would first organize cancer into a class of diseases called Karkinos that were similar to each other in ways he could not yet fully articulate.

Hippocrates interpretation of cancer is known to historians as the “Humoral Theory” in which medicinal treatment was based on balancing the 4 humors: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. Cancer was caused by an excess of black bile in the body. The humoral theory of cancer remained popular until the 19th century when scientific autopsies were becoming more common-place and microscopes had led to better understandings of cells as part of the human body.

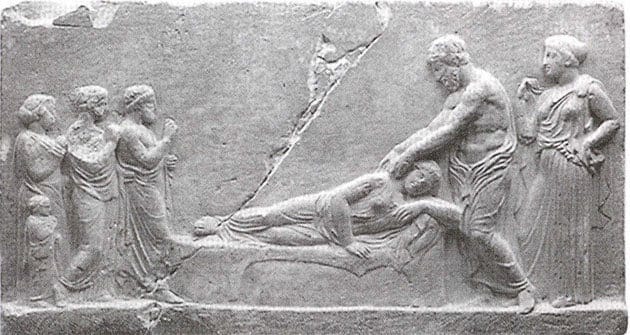

Unlike the other three humors, which unbalanced had varying degrees of medical concern, an overabundance of black bile was a death sentence. There wasn’t much physicians like Hippocrates could do for his patients but to send them home to die.

Siddartha Mukherjee writes in his book, The Emperor of All Maladies…

Cancer, Galen suggested, was the result of a systemic malignant state, an internal overdose of black bile. Tumors were just local outcroppings of a deep-seated bodily dysfunction, an imbalance of physiology that had pervaded the entire corpus. […] The black bile theory of cancer was so metaphorically seductive that it clung on tenaciously in the minds of doctors. The surgical removal of tumors—a local solution to a systemic problem— was thus perceived as a fool’s operation.

I find it amazing that with no knowledge of cells, or MRIs, or systemic medicines at all, that Galen and Hippocrates would understand cancer and metastasis so deeply. It’s almost like they guessed, and by the virtue of luck stumbled into the correct answer.

When cancer has metastasized to a different part of the body (a stage of the disease colloquially known as Stage IV) it is useless to cut the tumors out. They’ll grow right back. The cancer has surreptitiously spread through your blood, your bones, your lymph. In order to combat it in a meaningful way you need a medicine that kills it throughout your whole body, this is why chemotherapy (a systemic treatment) is the barbaric miracle that it is.

My tumor certainly didn’t look like a crab. Oddly enough I was complimented by various ultrasound techs as to how “regular” and “contained” my tumor appeared on imaging. A remark to which I had no response to other than “…thanks? I guess?”. I have absolutely no control over that.

This is also largely the reason why I was told by everyone before my biopsy that I shouldn’t be worried because the mass was benign. I suppose it’s rare for a tumor with such clean margins to be malignant. Crab-like or not, it certainly was cancer.

What can I say? I’m a rule-breaker at heart.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to A Body That Enjoys Itself to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.