Cancer on the Screen; A Non-Exhaustive Exploration

From Walter White's puzzling goatee, to tragic YA romance, to Star-Lord's martyr-complex mother.

Oh, to hell with your cancer. I’ve been living with cancer for the better part of a year. Right from the start, it’s a death sentence. It’s what they keep telling me. Well, guess what? Every life comes with a death sentence. So every few months, I come in here for my regular scan, knowing full well that one of these times– hell, maybe even today–I’m going to hear some bad news. But until then, who’s in charge? Me. That’s how I live my life.

― Walter White to a patient whose cancer has just been diagnosed.

When I was first diagnosed I had a friend with a non-cancerous chronic illness reach out to me to ask me some questions about the cancer care apparatus. One of the things that came up as a focus in our conversation is how the idea of cancer conjured something very specific in everyone’s mind–and mine especially having been newly diagnosed.

We all are walking around with subconscious expectations of what having cancer looks like, feels like–and we all have an understanding of how serious and life-threatening cancer as a disease is. My friend had never experienced that kind of concern for their chronic illness, which was often dismissed as unserious or dubious.

I began thinking about why this is. Why in our culture do we have such a deep understanding of cancer and what a cancer diagnosis portends, but not, say, endometriosis, or Crohn’s disease, or diabetes?

I thought often to my own experiences of my family members receiving cancer treatment and how viscerally difficult and near universal it was for most families. Was it a numbers game? Do simply more people deal with cancer than other chronic illnesses and that’s why we know it so intimately? Perhaps.

Or was it an incredibly, unbelievably successful marketing campaign that reached national renown and lodged itself into the American psyche for generations? Led by the noble pathologist, Sidney Farber in 1940’s Boston as he desperately searched for a cure to Leukemia for “Jimmy”, a blank placeholder for all the young children in his ward at the Children’s Cancer Research Fund, later named the Jimmy Fund… Could be also...

But I think my most specific (albeit often incorrect) notions of cancer and its treatment were formed by the media I consumed. In fact, when I was crying in my oncologist’s office (every time I was there). She would often say verbatim, “Chemotherapy is not like the movies.”

Often cancer is a plot device written into scripts to create martyrs and savior-complex characters that advance the motivation of the protagonist and lazily communicates their trauma.

When I think of this archetype I think of the Marvel movie Guardians of the Galaxy, and specifically Star-Lord’s mother, suffering from brain cancer in the hospital.

She’s reposed and kind as she gives Star-Lord the tape-player that becomes emblematic of the franchise. He refuses to hold her hand as she slips away, thus robbing her of a “good death” and cementing his survivor’s guilt for year’s to come.

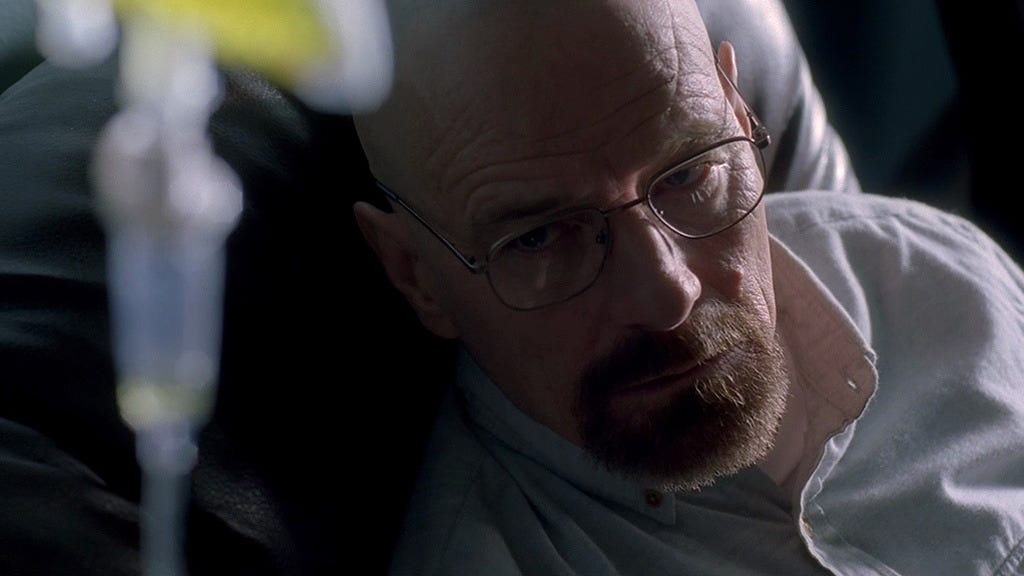

Then you have the opposite end of the spectrum where the audience often forgets that a character has cancer at all because they rarely seem affected by it unless the plot takes us to the hospital or the infusion center. I think of Walter White when I consider this archetype. A badass who’s too busy for cancer and has nothing left to lose.

Overall, I consider this a step up from the Guardians of the Galaxy cliché, because truly, many cancer patients aren’t very deeply affected by their treatment and can live relatively normal lives. You might never even know they have cancer. I will say that I do entirely blame Breaking Bad for giving me the wrong impression of infusion centers. I remember the sickly green hue of the infusion bags in the show and envisioned it as a dark nauseous place, full of suffering. While they certainly aren’t pleasant places to be, their inflammatory portrayal caused me a lot of stress.

The bait and switch of Breaking Bad is that Walter White’s meth-making escapades began as a way to pay for cancer treatment, but very quickly became an obsession with power and money. I think it’s purposeful that the audience loses sight of that along with Walter White. One more area, the audience loses sight of is the catalyst for the whole story, and later, it’s inevitable climax: Walt’s cancer.

I could probably write a whole essay alone about cancer in Breaking Bad, since it such a prominent yet background force in the story. I find it fascinating how the show-runners were able to walk that line, even if I don’t always think the portrayal was the best.

Lastly, I wanted to talk about an early-2010’s phenomenon that was the terminally ill YA romance books that seemed to take teen culture by storm. There’s The Fault in Our Stars a book-turned-movie about two cancer patients who meet-cute at a support group. There’s Me and Earl and the Dying Girl another book-turned-movie about a high-schooler who slowly and subtly falls for a friend battling Leukemia–who eventually decides to discontinue her treatment. I’ll be honest with y’all. I’m not sure how to unpack this one.

On the one hand, I can appreciate the interest in young adult cancer patients and their romantic lives (which don’t end when treatment begins!), as well as the very important coming-of-age messages for young people dealing with the trauma of their friends getting sick. But there’s also something about this trend that doesn’t hit me right. It seems to almost fetishize the drama and tragedy of cancer to pluck the heartstrings of romantic teens. The star-crossed lovers–doomed to death, but choosing to love anyway.

If I had to name a piece of YA media that I think does cancer representation extremely well, I would without a doubt say The Midnight Club. a book-turned-series directed by one of my favorite horror directors, Mike Flanagan. The story follows 8 terminally ill young adults in hospice who sneak out to take turns telling each-other scary stories late at night. It’s spooky, creative, emotional, funny, and extremely well researched.

Plus, I can’t get over Ruth Codd’s fiery, witty, and hilarious performance as Anya–an Osteosarcoma patient who struggles with addiction to the drugs prescribed to manager her pain. A silent and often ignored quandary in the medical treatment of cancer patients.

I’m of the opinion that perfect media representation doesn’t exist. It can’t exist. The issues and experiences that any number of identities or personalities can experience is as infinite and diverse as the population itself. You might find a character who speaks to you on a profound level, but likely someone else in your same community won’t feel the same way, or even further, feel misrepresented.

There’s a funny It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia meme that I endlessly quote: “Everything’s problematic, bitch. Let’s get you the ability to criticize media and still enjoy it”.

I honestly think about this meme a lot and use it as my guiding star when critiquing representation in media. What about you?

What do you consider to be good media representation of an identity or community? What other examples of cancer patients are there in media that I missed?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to A Body That Enjoys Itself to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.